Ugly buildings

Excerpt from the chapter "Ugly Buildings" from the book LAtitudes: An Angeleno's Atlas, by Wendy Gilmartin

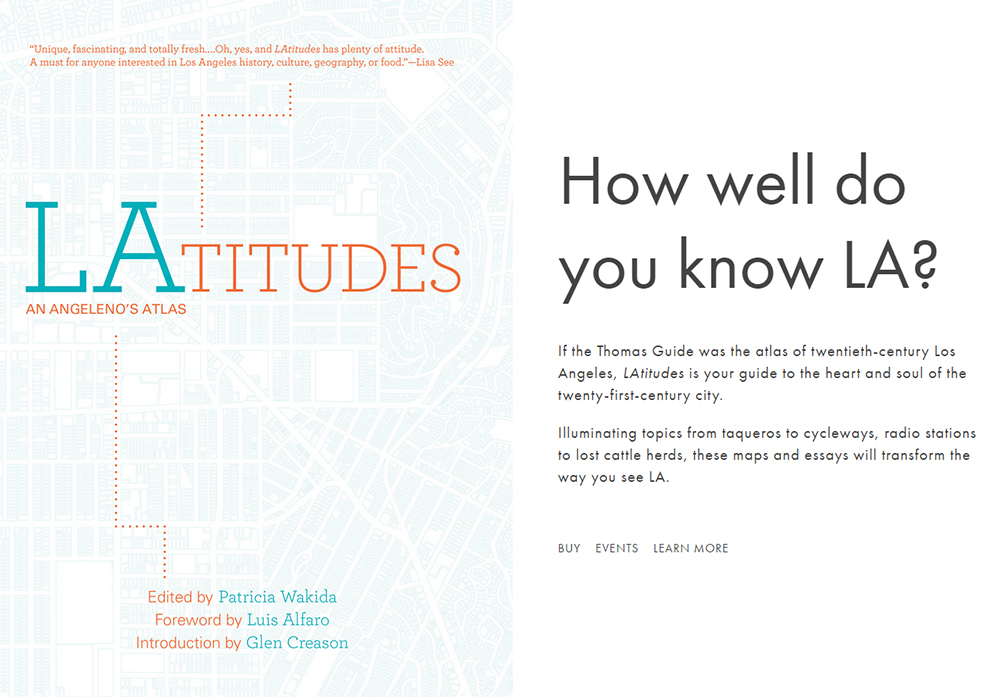

You can purchase LAtitudes: An Angeleno's Atlas from Amazon.

Travelers from all the world’s burgs, barrios, and banlieues touch down daily at LAX with Kodachrome visions of salty mists falling along Malibu’s beaches, newly waxed and gleaming immaculate cars, spray-tanned celebrities and mellow, purple-ish sunsets, only to emerge from the terminal and head up the 405, towards ever more slowly moving traffic. When they finally stop at a standstill between freeway exits and begin to look around, they’re met with the bare back walls of parking structures, identical grey condos peeking up from behind highway embankments, and black-windowed, soulless office towers. This relentless landscape of blah is what most visitors and many residents find visually unappealing about Los Angeles. “Why is LA so ...ugly?” they ask.

“The mountains,” we implore our visiting friends and family, “the beach, the hills, the bougainvillaea bushes, Chavez Ravine...! Those aren’t ugly!” It gets an Angeleno hot and itchingly defensive. But a proud Angeleno needs to simmer down because a hater’s gonna hate. Even the Los Angeles Times’s own architecture critic recently relented, “Much of what we lay our eyes on as we move through the city every day can be remarkably, even punishingly unattractive.” Those who dismiss ugly Los Angeles will snark at our traffic, overpriced restaurants, and attitude too. And they’ll never uncover the meaning and reward to be revealed in the city’s messy stew of urban elements. Los Angeles does have beautiful buildings. These are conceived by philanthropic boards of directors, and get reviewed by smart critics. They’re associated with high art and protected and preserved by conservancies. Beautiful buildings have had all their bugs worked out by historical trial and error, or by teams of specialists who meet frequently to discuss any functional or formal issues through the course of construction. They’re often situated in Edenic natural landscapes, standing massively in solid stone and rustic timbers. They have glorious culture and music and taste pouring from them, and they charge entrance fees. Folks tend to agree the historic houses of Hancock Park and Crenshaw are beautiful, as are midcentury desert ranch-style homes and the Bradbury Building on Broadway downtown. Other local crowd-pleasers include Lloyd Wright’s Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles City Hall, Pann’s diner on La Tijera Boulevard—the quintessential sixties incarnation of forward-thinking “Googie” design—and the Greene brothers’ artsand- crafts-era Gamble estate in Pasadena. These structures are exquisitely crafted, carefully kept, and honored.

Coasting through downtown, one takes in a visual index of a certain development type—the city core—where skyscrapers built in the 1970s and ’80s soar at towering heights. Their glassy, steely architecture symbolizes financial stability, capitalism, investment, permanence. Older towers from the 1920s and ’30s offer meticulous motifs etched in stone, arching entrances to ornate lobbies, and detailing in a style of elegant grandeur long lost in building craft today. Combined, these two types of downtown buildings provide Los Angeles its skyline and visual locus. But as one moves out from the city core in any direction—on Third Street, Mission, Central—the environment changes. The buildings out here symbolize something else entirely. This is the vast, horizontal mass of Los Angeles’s built ecology—a landscape of tacked-on siding and black glass, McMansions, yawn-worthy stucco apartments on tiny stilts, dumpy offices, monotonous parking structures, and sad strip malls. Out here amongst the lords of bad taste also lies the potential for a drastically different urban situation. Let the critics concern themselves with the architectural beacons of our contemporary times; ugly buildings are really where it’s at.

Errata

Credit is due to the following for research used in this chapter:

Fulton, William, The Reluctant Metropolis: The Politics of Urban Growth in Los Angeles; Johns Hopkins University Press 2001.

Chapman, Jeffrey, I. Proposition 13: Some Unintended Consequences, Public Policy Institute of California; September 1998.

Read the Reviews:

Oliver Wang, Los Angeles Times